- Home

- Kara Bietz

Sidelined Page 2

Sidelined Read online

Page 2

It was bad enough that I had to say goodbye to her after lunch and before her nap. She was cranky and upset with me, her dark curls sticking up in seventeen different directions while she made a mess out of a bowl of macaroni and cheese. I tried to help her, tried to guide the spoon to her mouth, but she wasn’t having any of that.

“No, Uncalijah,” she whined, stretching out her name for me into a million syllables. “I do it myself.” The tears started about halfway through the bowl. We had spent the morning playing in the little splash park near our apartment, and I knew all that running around in the sun and heat was going to leave her happy but zonked. Even waiting ninety seconds for Frankie to nuke a bucket of Easy Mac and warm up a few green beans left her curled in a ball in the kitchen with crocodile tears rolling down her cheeks.

I put her down for a nap after her lunch devolved into a long string of tired cries and whines that the macaroni was “too slippy.” Sticky golden cheese was still clumped on her chin and in her curls. It wasn’t the most charming way to remember her, but it still makes me smile as the bus pulls onto the highway, pointed south.

“Uncalijah will see you soon,” I told her, kissing her forehead, the only part of her face that wasn’t caked with powdered cheese.

“Nooooo,” she said, her eyes already closing.

“Text me pictures,” I said to Frankie when I left. “I’m sorry I’m leaving her with you like this.”

“A nap will fix her right up,” Frankie said, hugging me tightly. “We’ll be there soon.”

“Bye, Ma.” I waved toward the back patio, where she was surrounded by moving boxes and rolls of packing tape.

“Be safe, Elijah. Call us when you get there,” she said without getting up. “And you tell that Ms. Jackson thank you, you hear me? Her taking you in for a few weeks is the nicest thing someone from Meridien has done for us in years.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

Maybe it was going to be weird living with Ms. Jackson and Julian. Even if it was only for a few weeks. Who was I kidding? It was definitely going to be weird. But when Ma made the decision that we needed to get back to Meridien, there was no way I was going to start school again in Houston and then switch after three weeks. Ma got on the phone with Pastor Ernie, Figg, and Coach Marcus the same day she decided.

I was sitting in the living room the day Figg called her back.

“Really? Well… isn’t that something,” she said, a slight smile brightening her face.

A short pause.

“Well, you be sure and tell her thank you,” Ma said quietly.

A longer pause.

“I appreciate you both, Thomas. I’m sure Elijah will be thrilled. You’re right; they were friends for a long while.”

Friends? Did I ever have real friends in Meridien? I started to think about the things that happened there before we left the first time and—

“Please tell Pastor thank you, too.”

A twinge of sadness pulled at my chest, but I swallowed it down. I looked at my mother as she hung up the phone, some of the stress visibly falling from her shoulders.

“What am I going to be thrilled about?” I asked, setting down my book.

“Ms. Jackson has offered to take you in for a few weeks,” Ma said.

“Ms. Jackson? Julian’s grandmother?”

“Yes,” Ma said. “Isn’t that wonderful news?”

Wonderful isn’t what I would have called it that afternoon. Or even the next day or the next. I wouldn’t even really call it wonderful right this very second, but here I am on a one-way bus trip to Meridien with plans to be at Ms. Jackson’s house this evening.

School was sorted out with a few phone calls. Football, too. Coach Marcus agreed to let me come to practice and work out with the team as a sort of tryout, but he hinted that it was mostly a formality. I haven’t touched a football in three years, and I suspect I’m going to get a ton of mileage riding the bench, but it doesn’t matter. Being part of the team might be the thing I’m looking forward to the most about going back to Meridien. Or maybe the only thing; I don’t know. Some days it felt like a fantastic idea. And some days it felt like this was quite possibly the worst idea Ma has ever had, and that’s saying something.

“You okay with all of this?” Frankie asked me one night while I helped her give Coley a bath.

“Yes? No. Definitely maybe,” I told her.

“It will probably only be for a few weeks,” she said. “Ma can’t quit her job here until the first of the month,” she reminded me.

“I know. It’s just… Julian.”

Frankie lowered her head. “I get it. Maybe… maybe you could just walk in there and be your usual Elijah self and act like none of that ever happened? A clean slate is what you need,” she said.

I don’t necessarily agree that forgetting any and all bits of the past is the best plan for a new start, but I haven’t come up with anything better in the few days I’ve had to pack everything important into my biggest duffel bag.

I thought about Julian all the time. From that early morning three years ago when Frankie and Ma and I disappeared from Meridien until this moment right now as I sit on this bus, I’ve thought about him.

“Listen, don’t say anything about me and Coley while you’re in Meridien, okay?” Frankie told me right before I left.

“How come?”

She pursed her lips, and her eyebrows squinched up in the middle of her forehead. “I just don’t want people gossiping about me before I’m even there. It’ll be my story to tell when I get there, okay? Promise?”

“Yeah, okay. I promise,” I told her, even though I didn’t completely agree. Being a teenage mom shouldn’t make someone a pariah. “But God help anyone who’s got something to say about you,” I said, my hands balling into fists at my side.

“Hey, fresh start. Remember?” she said, grabbing my wrist and shaking my hand out of its fist.

I lean my head against the bus window and watch the broken white line stretch for miles. What was Julian doing right now? What was he thinking? Did he spend as much time remembering me as I spent remembering him?

Three weeks without Coley.

Three weeks with Julian.

I don’t know which I’m dreading more.

· three ·

JULIAN

“We’ve got a major weak spot on the left side,” Coach Marcus yells while we scrimmage. “Tighten up, boys!”

The center hikes the ball to me, and I back up a few steps, looking for an open pass. I spot an open receiver downfield about twenty yards, heading toward the end zone. I pivot right and let the ball go, watching it fall gently into his hands. Just as I exhale, I’m hit, hard, from the left. I fall to the ground in an ungraceful heap, my ribs buzzing.

“Late hit! What the hell was that!” I yell, pushing the defender off me. It’s one of our new guys, a freshman. He looks at me, eyes wide.

“I’m so sorry, Julian. I’m so sorry,” he says, his voice shaking. He extends his hand to me, but I smack it away.

“Good way to get yourself kicked out of a game, newbie,” I say, pulling myself up off the ground, my ribs burning. This kid is huge.

“It won’t happen again, Captain Jackson. I swear,” he says, talking around his mouth guard.

Captain Jackson. I snicker to myself as he lumbers away. “Captain Jackson” sounds like I’m the commander of the starship Enterprise. Coach Marcus introduced me as such to the freshmen on the first day of practice, but I’m still getting used to it.

“Last play! Make it count. Let’s stay on our feet out there, QB!” Coach yells from the sidelines, as if I fell down because I was clumsy. I twist a bit, try to get a little blood flowing to the pulsating pain on my left side. It’s stiff, but it’ll be okay. “Rub some dirt on it and get back in there,” my dad would’ve said.

I call for an easy play and set up, knowing I’m kind of copping out here, but I really don’t want to get hit again. I don’t exactly have a ton of confidence

in my offensive line yet. The center hikes the ball perfectly, and I make an easy handoff to my running back. The play goes as planned, and I back away from the defense as soon as I hand the ball over. The RB makes a valiant effort to get through, but the defense is just too strong for the wimpy play I called. He’s driven back a few yards for a gain of zero. Coach Marcus blows the whistle.

“That was no good. You had Connors wide open downfield, Julian,” he says as everyone trudges off the field, sweaty and out of breath.

“Yes, sir,” I answer, twisting a little.

“Don’t you do that to us on game day,” he grumbles. “Use your head out there.”

“Yes, sir,” I say again.

I stand by the big fan and grab a water bottle while the defensive coach, Andrews, trots over to Coach Marcus, shaking his head. With the loud fan blowing in my ear, I catch only snippets of their conversation.

“… gotta do something about that left side.” Coach Andrews removes his cap and wipes the sweat from his bald head.

From the few words I manage to hear over the fan, it almost sounds like we’re about to get a new player. Maybe they’re bringing someone up from the junior varsity to help out on that left-side defense. I keep my ear trained to their hushed conversation as I step away from the fan and collect the water bottles my teammates have tossed by the bench.

“We’ll see how it goes tomorrow.” Coach Marcus checks his watch.

Coach Andrews’s eyebrows pinch in the middle of his forehead. “I hope you’re doing the right thing,” he says, shaking his head again and putting his cap back on. The two of them walk toward the locker room.

“Want to throw a few for me?” One of my wide receivers, Nate Connors, taps me on the shoulder. “I want to run a few of the formations I’m having trouble remembering.” He spins a football in his palm.

“I can do that. Maybe we can also have some of the cheerleaders hold up the routes on giant posters during the games.” I grab the ball from his hand and jog away from him, knowing I’ll at least get a punch in the shoulder for that smart-ass remark.

“Jackass,” Nate says. He laughs and catches up to me, indeed giving me a solid punch in the shoulder.

My side burns a little bit while we’re working, but I’m putting it out of my head for a few minutes to help Nate. Especially if I don’t have to worry about getting nailed by a yeti-sized lineman while I throw him a few.

I call a couple of plays and help Nate remember the running routes, tossing some long bombs out to him as he runs toward the end zone. We connect on more than half by the time Nate decides he’s tired.

“Okay, I’ll call the cheerleaders and tell them to stop making posters. I think you’ve got a good handle on the routes,” I tell him as we collect the balls together. The lights overhead buzz in the late-night heat.

“You’re a real peach,” he deadpans with a smirk, throwing the full ball bag over his shoulder. “You think we’re ready for Stephens City?”

“Absolutely,” I tell him. “I don’t remember Crenshaw ever losing a game to them.”

“Taylor’s the real threat anyway. Everything leading up to that feels like a peewee scrimmage,” he says, laughing.

“Got that right,” I agree.

“So, what are we doing this year, Cap?”

“What do you mean, what are we doing? We’re playing football, we’re graduating, we’re—”

“Oh, come on, don’t mess with me.” Nate laughs again. “It’s our senior year! Don’t tell me you haven’t decided what pranks we’re pulling before homecoming. They’ve gotta be good and we’ve gotta strike first.”

“I haven’t given it a lot of thought, to tell you the truth.” It’s not my thing. The senior class always tries to pull off a string of outrageous pranks before the Taylor game. I always thought it was a stupid tradition. But in an even dumber tradition, those pranks have to be decided upon and led by the team captain.

As a senior who would like to eventually go to college without some prank-gone-wrong on his permanent record, I’d like to give the wiseass who came up with this a piece of my mind.

“My dad said that in his senior year, they filled the Taylor quarterback’s truck cab with popcorn. That’s not exactly the most epic prank, but he still remembers it.” Nate shrugs. “I guess I just hope it’s something we remember when we’re forty years old, you know?”

I get it. I do. I just don’t see why it’s up to me to figure out what’s going to be memorable enough. There’s this spirit of one-upmanship at Crenshaw, and I don’t know that I’m the right guy for that job. Last year’s seniors somehow figured out how to swap the cards the Taylor marching band was supposed to hold up that spelled out GO TITANS so that, instead, they spelled out CRENSHAW during their homecoming halftime show. How you top that, I have no idea.

Taylor usually gives as much as they get, too. They decorated the trees in front of Crenshaw in their school colors three years ago, and last year they somehow managed to kill off the grass in front of our gym in a pattern that spelled out TAYLOR TITANS.

And way back when, when my dad was still in school, they spray-painted their mascot onto all of our bleachers in red and black.

“Hey, if you think of something, how about you let me know?” I tell Nate on our way into the locker room.

“No way, man. That’s the captain’s job. I’m all in on whatever you decide, though,” he says, shuffling toward his own locker. “It’s on you, Cap.” Nate salutes me and then turns on his heel and marches across the room.

My ribs are really burning by the time I get in the shower. I try to talk myself out of it. If I can ice them and rest tonight while I’m finishing my English homework, I’ll be as good as new in the morning. But I’m still one of the last ones out of the locker room, and the drill team is getting out of their practice at the same time.

My best friend, Camille, catches me on my way out. Birdie says Camille can talk the hind legs off a donkey. Since I don’t usually have a lot to say, we’re a good match.

“How was your practice?” she asks, stretching her long frame and shaking her curls out of the tight ponytail they were in. She ties her Crenshaw County Guardettes satin jacket around her waist. I always wonder why they didn’t just call them the Guardswomen instead of the Guardettes. Seems like a lame name for a drill team.

“Probably about as good as yours,” I say, noticing how tired she looks.

“You’re walking funny; you okay?”

“Newbie made a late tackle, caught me off guard. I’m all right,” I say.

She raises her eyebrows.

“I’m fine, I swear. Tell me about your practice. You look like you’ve been hit by a truck,” I say, changing the subject.

“You’re not kidding,” she says, and starts in on a story about how Jannah Sykes took a tumble during the opening number and laughed and how they had to spend the rest of practice doing that one combination because the drill coach is a sadist and when you’re the one who has to do three back handsprings in the opening combination and you have to do it a million times until you’re so dizzy you can’t tell what’s the ceiling and what’s the floor, it can get annoying. Especially if Jannah laughs every time she falls, and Coach gets more and more mad.

I don’t think Camille breathes once while she tells me this story.

“Connors reminded me that I need to start thinking about the senior pranks,” I tell Camille when I can finally get a word in. To be honest, I half hope she has some brilliant idea that I can just steal and use.

“Ooh, what are you going to do?” Camille claps her hands in front of her like she’s a kid at the circus. “Coach still talks about the pranks the year she graduated, even though she said she’s supposed to discourage us from participating.”

“Oh, yeah? What happened in her year?”

“Well…” Camille starts, throwing her arms out wide in a dramatic gesture. “Hey, wait a minute.” She stops midstride. “You’re just fishing for ideas.” She

wags a finger at me and starts walking again. “I know how you operate, kid. None of that. They all have to be your idea. Otherwise it makes it less special.”

“Less special? Oh, come on, Camille,” I say. “You know this isn’t my thing. You gotta help me out!”

“Loosen up,” she says, shaking my shoulder while we walk. “It’s supposed to be fun. You remember fun, don’t you? It’s that thing you used to have in elementary school? Before this happened?” She gestures around me with her hands like a mosquito is buzzing nearby.

“What? Before what happened?”

“This,” she says, gesturing again. “This Mr. Study Until We Die stuff. This Mr. No Fun Until the Work Is Done stuff. Before that.”

“Oh, you mean before I realized there’s a great big world outside of Meridien?” I ask sarcastically. “Before I decided I wanted to be a part of it? Before I knew that the only way to make that happen is to work my ass off and maybe get a scholarship? Before all that?”

Camille rolls her eyes. “Oh, calm down, Juls. I’m just saying—this prank thing isn’t supposed to be some anxiety-inducing mess. It’s just a laugh. Stop worrying about it! Something will come to you.” Her grin turns mischievous. “But it better come to you quick.”

I set my jaw, and we walk all the way to the corner of Rudy Street without talking. Camille is always on my case about loosening up. But I didn’t get to be the captain of the football team by loosening up. Or into four AP classes.

Most of the kids from my side of the county end up in one of three places:

1. Stuck in some dead-end job in Meridien working for crap money.

2. Locked up or on probation for doing something they thought was going to be fun but was actually just stupid.

3. Out of here with a scholarship and a gold-lined path to bigger and better things.

As much as I love Meridien, I’m going for option three. And I’m too close to my gold-lined path to throw it all away for some stupid town tradition.

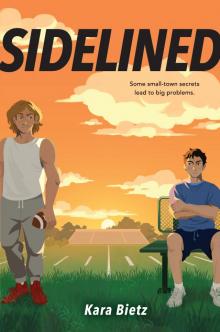

Sidelined

Sidelined